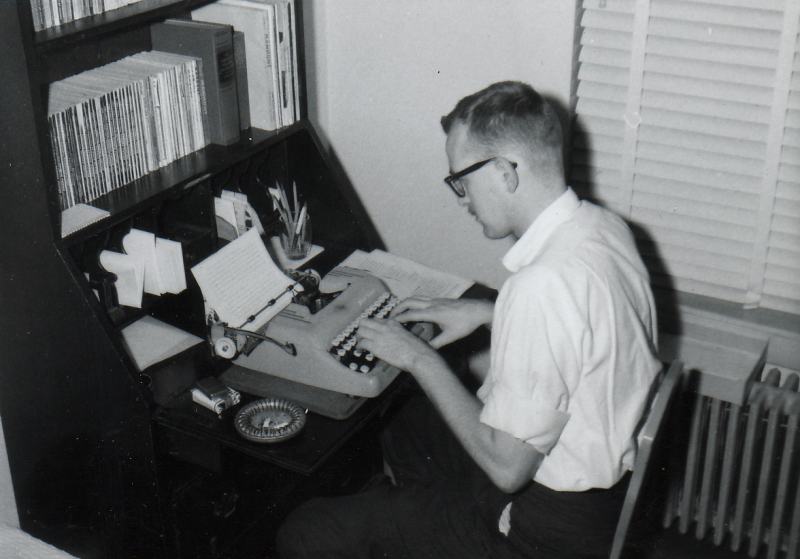

Don (center) doing the interrogating.

I think I’d best treat this as an interrogation, in which I am not certain of the intent or attitude of the interrogator.

I was born Donald Edwin Westlake on July 12th, 1933 in Brooklyn, New York. My mother, Lillian, maiden name Bounds, mother’s maiden name Fitzgerald, was all Irish. My father, Albert, his mother’s maiden name being Tyrrell, was half Irish. (The English snuck in, as they will.) They were all green, and I was born on Orangeman’s Day, which led to my first awareness of comedy as a consumer. I got over the unfortunate element of my birth long before my uncles did.

My mother believed in all superstitions, plus she made some up. One of her beliefs was that people whose initials spelled something would be successful in life. That’s why I went through grammar school as Dewdrip. However, my mother forgot Confirmation, when the obedient Catholic is burdened with yet another name. So she stuck Edmond in there, and told me that E was behind the E of Edwin, so I wasn’t DEEW, I was DEW. Perhaps it helped.

I attended three colleges, all in New York State, none to much effect. Interposed amid this schooling was two and a half years in the United States Air Force, during which I also learned very little, except a few words in German. I was a sophomore in three colleges, finally made junior in Harpur College in Binghamton, NY, and left academe forever. However, I was eventually contacted by SUNY Binghamton, the big university that Harpur College had grown up to become. It was their theory that their ex-students who did not graduate were at times interesting, and worthy to be claimed as alumni. Among those she mentioned were cartoonist Art Spiegelman and dancer Bill T. Jones, a grandfaloon I was very happy to join, which I did when SUNY Binghamton gave me a doctorate in letters in June 1996. As a doctor, I accept no co-pay.

I have one sister, one wife and two ex-wives. (You can’t have ex-sisters, but that’s all right, I’m pleased with the one I have.) The sister was named by my mother Virginia, but my mother had doped out the question of Confirmation by then–Virigina’s two and half years younger than me, still–and didn’t give here a middle name. Her Confirmation name was Olga, the only thing my mother could find that would make VOW. The usual mother-daughter dynamic being in play, my sister immediately went out and married a man whose name started with B.

My wife, severally Abigail Westlake, Abby Adams Westlake and Abby Adams, which makes her three wives right there, is a writer, of non-fiction, frequently gardening, sometimes family history. Her two published books are An Uncommon Scold and The Gardener’s Gripe Book.

Seven children lay parental claims on us. They have all reached drinking age, so they’re on their own.

Having been born in Brooklyn, I was raised first in Yonkers and then in Albany, schooled in Platttsburgh and Troy and Binghamton, and at last found Manhattan. (At least I was looking in the right state.) Abby was born in Manhattan, which makes it easier. We retain a rope looped over a butt there, but for the last decade have spent most of our time on an ex-farm upstate. It is near nothing, which is the point. Our nearest neighbor on two sides is Coach Farm, producer of a fine goat cheese I’ve eaten as far away as San Francisco. They have 750 goats up there on their side of the hill. More importantly, they have put 770 acres abutting our land into the State Land Conservancy, so it cannot be built on. I recommend everybody have Miles and Lillian Cann and Coach Farm as their neighbors.

[Below is an excerpt from Contemporary Authors: Autobiography Series, Vol. 13]

I knew I was a writer when I was eleven; it took the rest of the world about ten years to begin to agree. Up till then, my audience was mainly limited to my father, who was encouraging and helpful, and ultimately influential in an important way.

Neophyte writers are always told, “write what you know,” but the fact is, kids don’t know anything. A beginning writer doesn’t write what he knows, he writes what he read in books or saw in movies. And that’s the way it was with me. I wrote gangster stories, I wrote stories about cowboys, I wrote poems about prospecting–in Alaska, so I could rhyme with “cold”–I wrote the first chapters of all kinds of novels. The short stories I mailed off to magazines, and they mailed them back in the self-addressed, stamped envelopes I had provided. And in the middle of it all, my father asked me a question which, probably more than any other single thing, decided what kind of writer I was going to be.

I was about fourteen. I’d written a science-fiction about aliens from another planet who come to Earth and hire a husband-wife team of big-game hunters to help them collect examples of every animal on Earth for their zoo back on Alpha Centauri or wherever. At the end of the story, they kidnap the hero and heroine and take them away in the spaceship because they want examples of every animal on Earth.

Now, this was a perfectly usable story. It has been written and published dozens of times, frequently with Noah’s Ark somewhere in the title, and my version was simply that story again, done with my sentences. I probably even thought I’d made it up.

So I showed it to my father. He read it and said one or two nice things about the dialogue or whatever, and then he said, “why did you write this story?”

I didn’t know what he meant. The true answer was that science-fiction magazines published that story with gonglike regularity and I wanted a story published somewhere. This truth was so implicit I didn’t even have words to describe it, and therefore there was no way to understand the question.

So he asked it a different way: “What’s the story about?” Well, it’s about these people that get taken to be in a zoo on Alpha Centauri. “No, what’s it about?” he said. “The old fairy tales that you read when you were a little boy, they all had a moral at the end. If you put a moral at the end of this story, what would it be?”

I didn’t know. I didn’t know what the moral was. I didn’t know what the story was about.

The truth was, of course, that the story wasn’t about anything. It was a very modest little trick, like a connect-the-dots thing on a restaurant place mat. There’s nothing particularly wrong with connect-the-dots things, and there’s nothing particularly wrong with this constructivist kind of writing, a little story or a great big fat novel with nothing and nobody in it except this machine that turns over and at the end this jack-in-the-box pops out. There’s nothing wrong with that.

But it isn’t what I thought I wanted to be. So that question of my father’s wriggled right down into my brain like a worm, and for quite a while it took the fun out of things. I’d be sitting there writing a story about mobsters having a shootout in a nightclub office–straight out of some recent movie–and the worm would whisper: Why are you writing this story?

Naturally, I didn’t want to listen, but I had no real choice in the matter. The question kept coming, and I had to try to figure out some way to answer it, and so, slowly and gradually, I began to find out what I was doing. And ultimately I refined the question itself down to this: What does this story mean to me that I should spend my valuable time creating it?

And that’s how I began to become a writer.

Interview: Westlake vs Stark…